Afghan families start U.S. resettlement process at repurposed conference center after traumatic ordeals

Leesburg, Virginia — At the makeshift clothing store, outfitted with a mix of traditional Afghan garments and American clothes including jackets, socks and underwear, a young Afghan boy flashed a bright smile as he selected his first pair of outdoor boots.

Inside the recreation room, children played table hockey, took turns hurling a soccer ball in the air and contested boisterous foosball matches while Afghan music played in the background. A young Afghan boy ran around with a soccer ball, showcasing his skills to a news cameraman who followed him across the room.

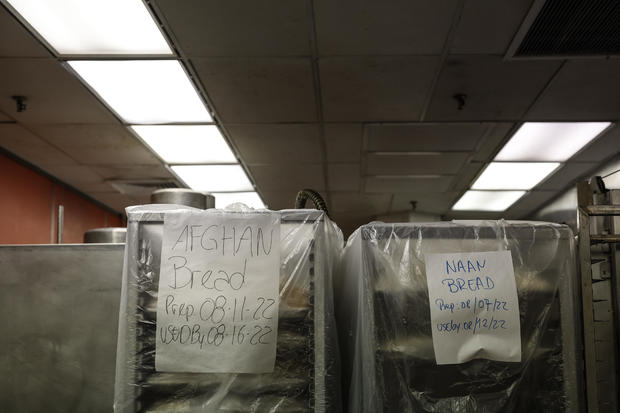

At the large dining area, which can seat 800 individuals, Afghan adults and families with minor children enjoyed Afghan cuisine staples, such as a kidney bean stew known as lubya, and Naan, as well as halal versions of American classics, including turkey hot dogs with beef chili.

In an arts-and-craft room adorned by dozens of paintings and drawings, children sat side-by-side drawing. Some had drawn animals, their favorite soccer team and Afghanistan’s flag. In drawings and paintings placed across the facility, children also depicted the American flag and expressed gratitude for their host country.

“Thanks to the United States of America,” read one child’s drawing of the American flag.

On Thursday, when a small group of journalists toured the site, the National Conference Center in northern Virginia was housing 657 Afghan evacuees selected for U.S. resettlement, including 216 children, according to data provided by officials from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which oversees the facility.

The massive hotel-like suburban complex, which typically hosts corporate and government events, was converted into a short-term refugee housing facility by the U.S. government earlier this year, becoming the sole domestic processing site for Afghans who escaped Taliban-controlled Afghanistan.

Last year, the Biden administration evacuated and resettled more than 70,000 Afghans, setting up processing hubs at military bases overseas and in the U.S. mainland where evacuees underwent security vetting, vaccinations, medical checks and immigration casework. The last processing site at a domestic military base closed in February.

Since then, the National Conference Center, which can house up to 1,000 individuals, has become the sole destination for Afghans arriving in the U.S. under the parole authority, which allows officials to expedite the entry of immigrants who have not yet completed the visa or refugee process on humanitarian grounds.

Since it was set up, the complex in Virginia has received approximately 4,300 Afghans, the vast majority of whom have been resettled by nongovernmental organizations responsible for helping new arrivals secure housing, government benefits, jobs and basic necessities, according to DHS statistics.

On average, the conference center receives a few hundred evacuees on one flight each week, typically from the United Arab Emirates, where thousands of evacuated Afghans have been stuck for months, said Kenneth Graf, a DHS official in charge of the facility. The last flight is set to arrive at the end of September, when the congressional funding for the site is slated to expire, Graf added.

John Lafferty, a senior DHS official leading a team tasked with facilitating the resettlement of evacuees from Afghanistan, said the U.S. is winding down its use of parole to admit Afghan evacuees, but stressed that other legal immigration pathways, such as the refugee program, would continue to be available to Afghans.

“The government’s commitment to our Afghan allies will continue well beyond today, and beyond the coming weeks and months,” Lafferty told reporters Thursday. “It will continue for the next several years as we try to make sure that we protect all of our allies.”

The facility is akin to a small town, equipped with 916 bedrooms; a mosque; a library; a reception desk; classrooms that offer English-language instruction, cultural training and technology help; an information center; a soccer field; a volleyball court; and a medical clinic staffed by 100 employees, including doctors, nurses and behavioral health specialists.

The hallways, bedrooms and common areas have signs in English, Pashto and Dari, and a cohort of translators and Afghan-American volunteers roam the complex to assist evacuees who don’t speak English. Most activities and services are divided by gender to avoid cultural misunderstandings.

In all, the conference center is staffed by more than 500 workers from refugee resettlement groups and the U.S. government, including U.S. service members and officials from the Department of Homeland Security, the State Department and the Department of Health and Human Services.

One room was converted into a hub for coronavirus testing, which all evacuees must undergo at intake. Michael Stanley, the chief medical officer at the facility, said his staff has administered over 15,000 COVID-19 tests on Afghans, noting evacuees are encouraged to continue taking tests on a weekly basis.

In another room, a handful of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) employees review work permit applications from Afghans, collecting biometrics, including fingerprints and photos, and adjudicating the cases on site so that evacuees can seek employment after leaving the conference center.

The complex also hosts a group of immigration lawyers who assist Afghans, either individually or in groups, as they navigate the byzantine U.S. immigration system and determine what programs could allow them and their family members to gain permanent legal status in the future.

While parole allows Afghans to work and live in the U.S. for two years without fear of deportation, it does not provide them a pathway to permanent residency. These so-called parolees must apply for other benefits, such as asylum or a Special Immigrant Visa for those who aided U.S. forces, to gain permanent status.

Earlier this week, a bipartisan group of House and Senate lawmakers introduced the Afghan Adjustment Act, which would allow evacuees who were paroled into the country to secure permanent residency after additional vetting. But if the measure does not pass the divided Congress, tens of thousands of Afghans could find themselves in legal limbo.

Ahmad, 30, who has been living at the National Conference Center with his family since August 2, said he still can’t believe he’s on U.S soil, noting he and his family members almost lost their lives trying to escape Afghanistan.

On August 16, 2021, Ahmad, who worked for a U.S. Department of Defense contractor that helped American military forces fight Taliban militants for two years, traveled to Kabul’s airport with his wife, who was pregnant at the time, and his elderly mother and sister.

When they were approaching one of the entrances, Ahmad, who requested his first name to be omitted, said he heard a loud bang. “When I turned around, I saw body parts of people in the air,” he recounted, becoming visibly emotional. “I was thinking, ‘this might be my last moment.'”

That suicide attack killed scores of Afghan civilians and 13 U.S. Marines, and fueled chaos around the airport. Ahmad said his mother fell to the ground. After he picked her up, his wife also fell. Fearing for his family’s safety, Ahmad said he decided it was too risky to try to enter the airport again.

Ahmad and his family, he added, spent weeks in hiding before traveling to an airport in Mazar-i-Sharif, a city in northern Afghanistan where some nongovernmental organizations were evacuating Afghans. On October 1, 2021, a U.S. military veteran whom Ahmad had worked with helped his family get on an evacuation flight to the United Arab Emirates.

Ahmad and his family members spent months in the Emirates Humanitarian City in Abu Dhabi, alongside thousands of other Afghans. He called it an “information blackout,” saying it wasn’t until a key part of his special immigrant visa application was approved in May that his family was considered for U.S. resettlement.

But even then, Ahmad struggled to secure U.S. resettlement for his mother and sister, who, unlike his wife and son, could not be included in his special immigrant visa case. Last month, however, U.S. officials agreed to resettle the entire family, and they landed in Dulles International Airport on August 2.

“It’s not an exaggeration. When I landed in the U.S., I felt at home. I felt safe,” Ahmad said, noting he used his baby boy’s hand to gently slap himself to make sure he was not dreaming.

Refugee caseworkers at the National Conference Center are currently determining where in the U.S. Ahmad and his family can resettle. He said his favorite memory so far in the U.S. is when staff at the conference center welcomed the bus that transported his family to the facility with American flags.

“It was so beautiful,” he said. “It is indescribable, my feelings.”